The aim of this blog is to put to bed a few misconceptions that continue to circulate in the world of Revit families:

That Revit has improved so much, there is no longer a concern about how families can affect Revit’s performance.

That over-detailed families don’t have negatively impact projects.

That paying attention to family file size is old-fashioned thinking.

At Kinship, our backgrounds are multidisciplinary. I personally bring over 20 years of experience coordinating and drafting building services, and around half of that time was spent on site, working directly with contractors and subcontractors. I’ve delivered numerous projects involving complex plantrooms and boiler rooms, leading coordination teams through very densely serviced spaces.

Anyone who’s been in those environments knows what happens. The model slows down. Navigation becomes sluggish. Views take longer to update. Drawing production becomes harder than it needs to be. And there’s nothing worse than having a big moody subcontractor standing over your shoulder, demanding to see coordination on screen while Revit crawls.

Over the years, most of us have learned to adapt. We split models, use worksets, crop views, apply view ranges, section boxes, hide categories, isolate elements, and cut sections so we’re only looking at the bare minimum of what we actually need. That’s all part of the basic setup on busy projects and it exists for a reason.

But there’s a growing school of thought which says that, because software and hardware have improved so much, we no longer need to keep that discipline. The idea being that we can start pushing unnecessary detail back into families—modeling everything “because we can”—and that it won’t have a real impact. But the reality is that it very much still does.

What leads to over-detailing in the first place?

There are a few common reasons that families end up being overly detailed:

The user doesn’t know the working scale of Revit models. So they think the level of detail is appropriate to what will be seen.

Flight of fancy. All those details sure look good in a render!

Misunderstanding priorities. The user doesn’t understand how a family actually gets used in design and deliverables, what exactly gets scheduled and how, and who benefits from the detail.

Why over-detailing still impacts performance

The fact is that the amount of geometric detail in a family still slows down Revit’s performance when it comes to model navigation and manipulation.

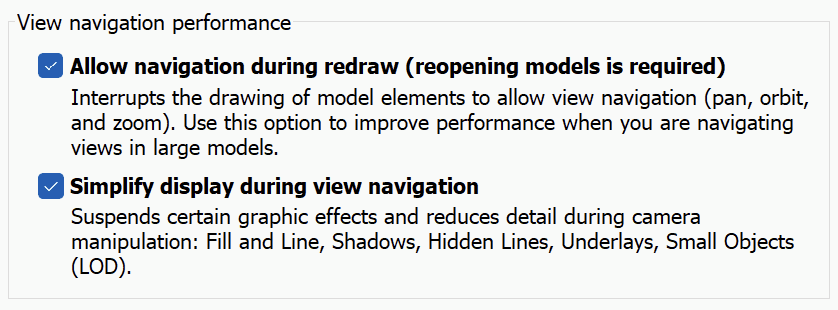

It is also true that Revit has made changes to improve navigation performance, most notably within the Graphics settings shown below. But these improvements don’t eliminate the impact of over-detailing.

To demonstrate this, we did a simple test using two models. The first model was populated with an overly detailed gate valve, while the second model uses a simplified counterpart. Both valves are suitable for fabrication and coordination since they both have the correct dimensions.

In the video below, we select 1000 instances of each valve. With wireframe enabled and no additional information in the model other than the valves themselves, the overly detailed valve takes more than twice as long to select, roughly 10 seconds. Selection is just one example, but it is a critical operation in daily workflows, second only to navigation in terms of how frequently it is used.

This is something that has always been acknowledged by Autodesk.

The difference comes down to performance versus appearance. The detailed valve can look better in VR and some fabrication views, but it is slower to work with. It will also be more difficult to work with, because it has more instance parameters that need controlling. It can even be argued that it looks worse in deliverables. Which leads us to more reasons to avoid over-detailing…

Over-detailing also wastes time and negatively impacts deliverables

Performance aside, there are other reasons to avoid over-detailing in your Revit families.

One is that it’s simply a waste of time. If the detail in a family is not going to be shown on a drawing, isn’t helping with design or deliverables, or won’t be consistently used, then what is the point of adding it? That’s time that could be better spent elsewhere.

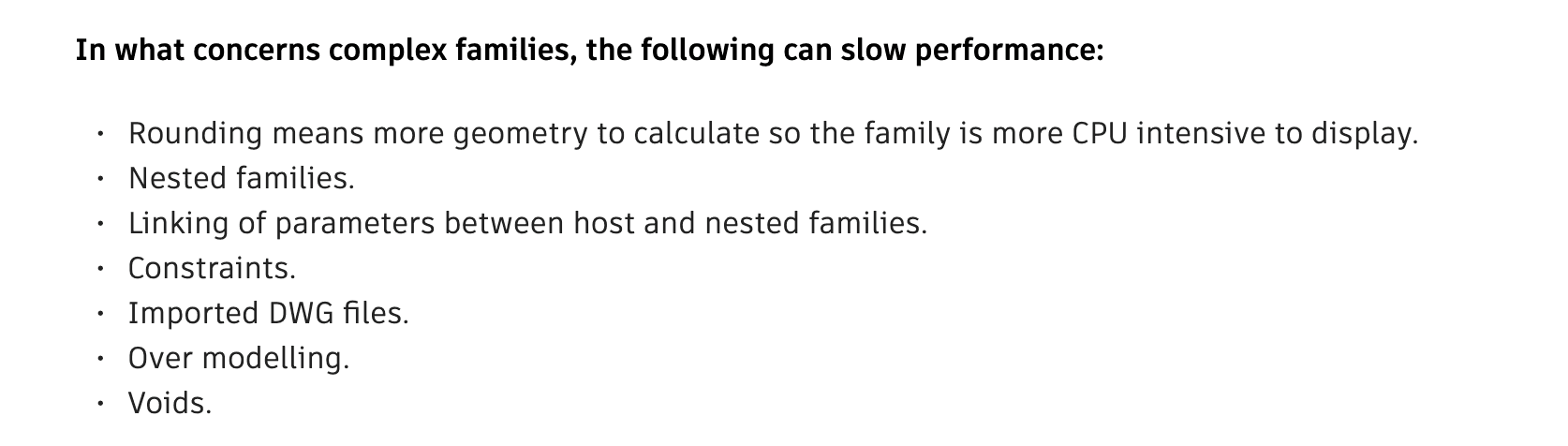

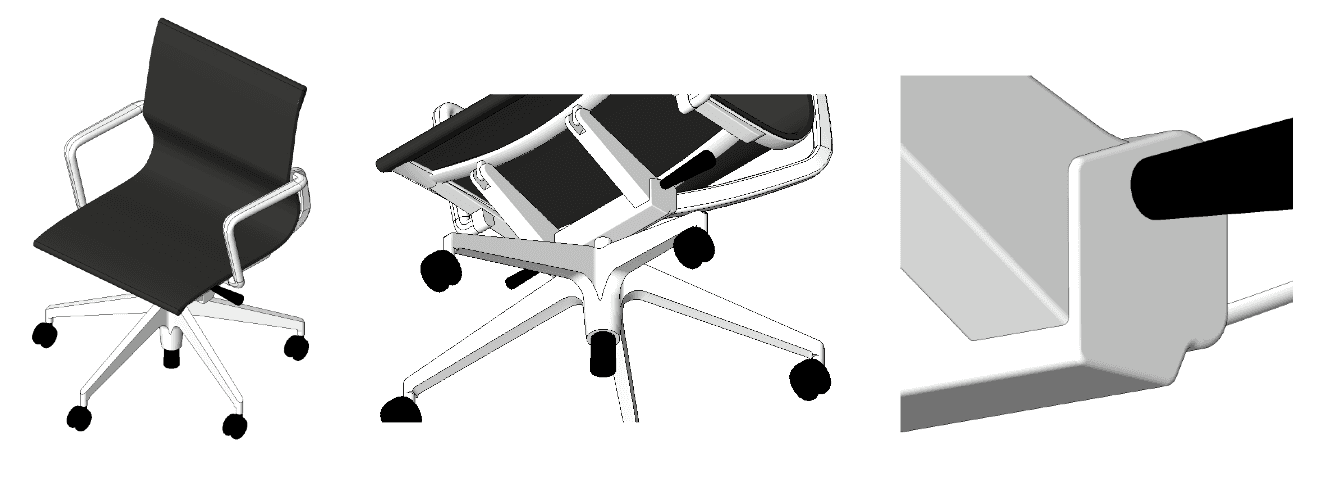

Below, we have two furniture families sourced from manufacturers. In both cases, there is an excessive amount of detail (and therefore time) that has gone into the base of the chairs. These details would be hidden in plan view and most 3D views, and will only show up in section or elevations. This detail and time would have been better spent on improving the geometry for the seat, backrest and armrest.

Another reason to avoid over-detailing is that it leads to lower quality deliverables. Below is an image showing two butterfly valves – one from a manufacturer and one we created – with actuators at hidden line view, replicating what you would typically see on a drawing. This is somewhat subjective, but I would argue that the Kinship version leads to better documentation. I’ve always preferred a cleaner look to my drawings, as the focus should be on coordination and services, not specific valves and certainly not actuators.

Lastly, over-detailing makes a family more difficult to use, which leads to both wasted time and lower quality deliverables. Extra details usually come with various parameters to control them, which can easily confuse users or get applied incorrectly. In any case they will require more time from the user to figure out.

What about detailing for fabrication?

Within the world of MEP, some people argue that you need additional detail in order to use Revit for fabrication. However Revit is a building‑scale design and coordination tool, not an Inventor‑style fabrication tool. So you don’t need fabrication‑level geometry in your Revit families (e.g. flange holes and screw relief) in order for Revit to do its job properly.

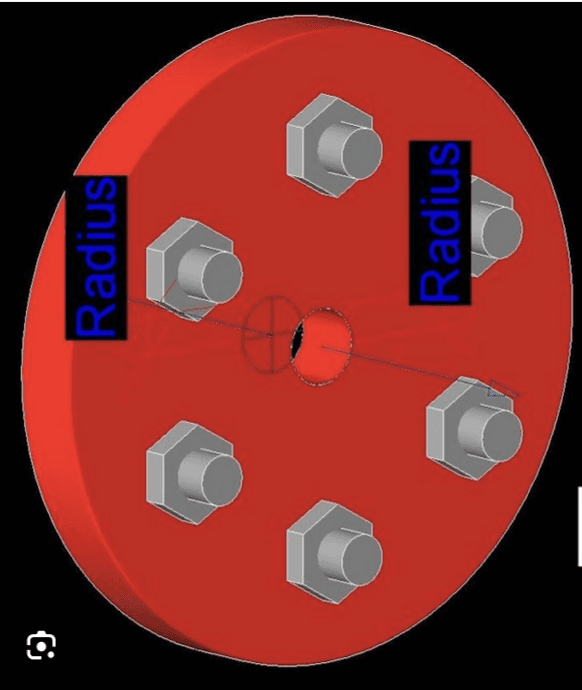

For spooling and fabrication, what matters for a valve is that the family has correct connection dimensions so the pipework is fabricated accurately. If you want bolts to be shown on your spool drawing, then nest a bolt family to the flange. Then it can be quantified. But the bolt holes themselves in the valve are not visually needed and not scheduled.

When actual fabrication logic is required, then Fabrication MEP is the right tool to use. It handles solder gaps, thread insertion, stock lengths and cut optimization, and BOM accuracy in ways that Revit families cannot and should not try to emulate. Revit families should stay light and dimensionally correct for coordination and spooling. If a project truly requires fabrication‑grade outputs, then that’s the point where you move into Fabrication MEP rather than stuffing fabrication detail into Revit families.

Using pipework as an example, the best argument in favor of over-detailing would be to create LOD400+ parts (e.g. a flange), so that you can schedule bolts and have them looking pretty in a spool drawing. But even then, there are levels to the game.

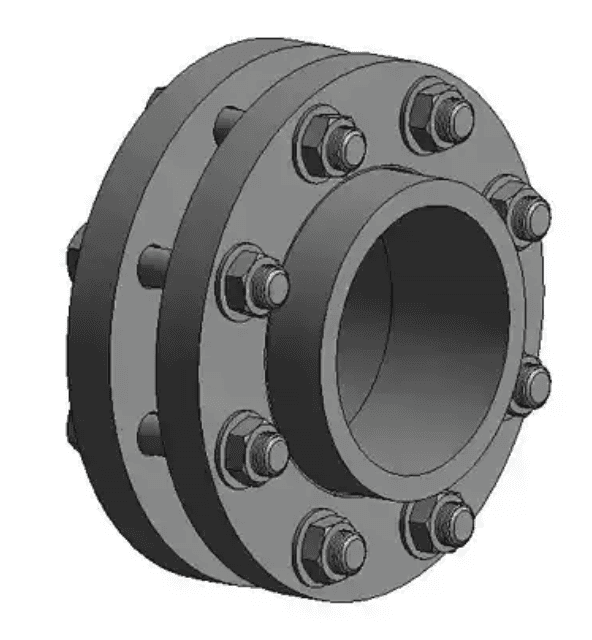

Below are images of two flange families. Both can look good on a fabrication drawing and schedule bolts and nuts. But one of them has twice as many faces for Revit to deal with. It should be obvious which one would be the preferred option.

Our preferred option.

Conclusion

At the end of the day, good Revit modeling is not about how much geometry we can squeeze into a family. It is about clarity, coordination, and efficiency. If a drawing is not clearly readable, the coordination behind it does not matter. Every modeling decision should answer the same questions: Does this improve coordination? Does it help deliver the project faster? Does it save time? Does it save money?

Even if newer versions of Revit can tolerate heavier content, that still does not make unnecessary detail a good idea. Time spent modeling bolt holes is time that could be better spent on something that will actually improve coordination, fabrication, and deliverables.

And building design and construction is a group effort. One over-detailed family may not cause problems on its own, but when multiplied across hundreds or thousands of instances and combined with similar decisions across architecture, structure, and MEP, models become harder for everyone to work with.

Models today are richer than ever, and rightly so. We add detail to improve coordination, support visualization, and meet modern project requirements. That is valuable detail. What is not valuable is geometry that adds no functional benefit.

The smart approach now is the same as it was years ago and the same as it will be in the future: keep families light, easy to use, and dimensionally accurate. Add detail where it serves a purpose. Leave it out where it does not.

Author

Chris Constantinou

Reading time

9 min

Share